A Warm Welcome

World War I Troop Trains in Huntington

By James E. Casto

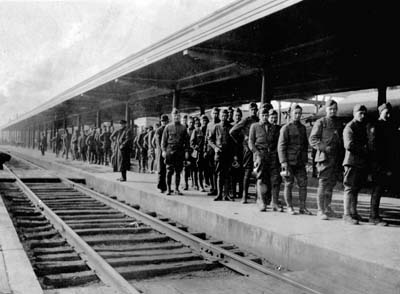

World War I enlistees line up at Huntington's C&O Railway Station as they wait to be fed at the station's Red Cross canteen. All photos courtesy of Marshall University Library, Special Collections.

When the United States declared war against Germany on April 6, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson urged his fellow citizens to help the newly formed American Red Cross assist the thousands of young men joining the Allied forces on the battlefields of Europe. The Red Cross responded in a number of ways but surely the most widely known and longest remembered was by providing coffee, snacks, and personal items for members of the military crisscrossing the country on troop trains.

During the war and for months after the fighting ended, Red Cross volunteers—almost all women—operated 700 canteens at railroad passenger stations across the nation, with several in West Virginia. One of the busiest was in Huntington, at the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway station at 7th Avenue and 9th Street.

The Huntington canteen opened on September 9, 1918, and closed exactly a year later. Even though the Armistice ended the war just two months after the canteen opened, the troop trains kept coming, carrying thousands of men on their way home or, in some cases, to a hospital. So the canteen workers remained on the job to help them.

A small army of 650 volunteers worked at the Huntington canteen under the direction of Lula Wellman Mossman, the canteen’s commandant, who was the wife of prominent Huntington businessman Dan A. Mossman.

In the early months of the war—before the canteen opened—Lula and a group of her friends had met in the basement playroom of her 6th Avenue home to make bandages for the wounded. When the Huntington chapter of the Red Cross set about opening its canteen, she was a logical choice to take charge.

The Huntington Lumber & Supply Company donated a small wood building that was moved to the C&O station. Volunteers had to be at least 23 years old. They were divided into groups and strictly scheduled. Each woman had to be certified by the Red Cross and outfitted in a long white uniform, with a white apron and head covering with the Red Cross emblem. A volunteer motor corps was organized for those who had no way of getting to the station and then back home.

The troop trains pulled into the station for a brief stop at all hours of the day and night, and a dozen or more women met every train, even those that arrived at 3 a.m. or so. The women prepared the food, cleaned the building (known as “the hut”), and boarded the trains—inviting the men to come to the canteen and serving the wounded who couldn’t leave the train.

The food was plain but hearty—sandwiches, homemade cake or pie, candy, fruit, milk and, of course, coffee. The women also passed out free cigarettes, pipe tobacco, magazines, and postcards. At the canteen’s peak, the women served an average of about 5,000 men a week. The record for one day: 2,333 men.

Food was donated by townspeople and local businesses. Others donated money so the volunteers could buy what was needed. Almost daily, Huntington’s newspapers published lists of donors and what they had supplied. On a day when three troop trains had gone through, the list included 39 people who’d made contributions, large and small—a jar of jelly, one or more pies, quantities of milk, two dozen eggs, and three dozen doughnuts, plus gifts of money.

At one point, the canteen was notified to expect 700 soldiers for supper. The meal was served at the National Guard Armory. Most of the food was donated. One hotel supplied the meat and another hotel the vegetables. Plates and silverware were loaned by stores, and the soldiers were served by 70 canteen volunteers.

The Red Cross enthusiastically praised the cooperation of the C&O: “They arrange to let the boys stay here as long as possible every time.”

The commanding officer of one train refused for his men to be served at the canteen, saying they needed exercise more than food. He then proceeded to march them up and down the street.

The canteen had its share of poignant moments, as reported in the daily newspapers. For instance, one soldier, after realizing he was in Huntington, remarked that he had a brother he hadn’t seen in years who worked at C. M. Love Hardware. A bystander hurried off to the hardware store and, shortly before the troop train pulled out, returned with the soldier’s brother in tow. The two men hugged and had a great reunion, while the crowd cheered.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.