From Candles to Carbide

Early Mine Lighting in West Virginia

By Jim Lackey

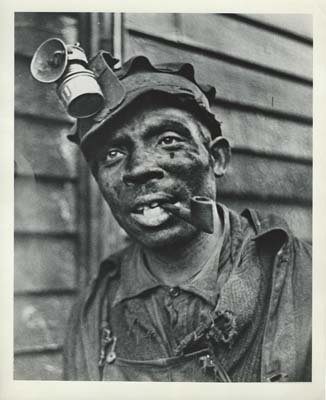

Miner with carbide lamp, date and location unknown. Photograph courtesy of the Eastern Regional Coal Archives.

If you were an underground miner in the late 19th and early 20th century, light was as essential as food and water. When railroads opened up the coalfields of West Virginia, most underground mining was done with the aid of some form of open-flame lighting. Safety lamps were in use at this time and were used for gas detection, but working by them was not an easy task.

The small “teapot” style lamp was used in the eastern Unites States; western and hard-rock miners preferred candles and candlesticks. European miners emigrated to the U.S. in great numbers at this time, and many brought their lamps with them. American miners adopted this type of lighting, and this gave rise to another industry, that of supplying the demand for lamps and fuel. Several manufacturers began supplying this need. Some were involved in the lamp trade only; some were part of larger manufacturers. There was also a large cottage industry developed, as any good tinsmith could make a wick lamp – many were very proficient at their trade.

Some form of liquid or semi-liquid was used for fuel. Mineral oils, animal fat, vegetable and seed oils were common, as were several manufactured oils and home concoctions. Some fuels smelled or smoked so terribly that several states outlawed them and set standards for lamp fuels. One common fuel was a paraffin wax substance that miners could whittle or shave from a solid block.

Usually called Sunshine, it was popular with miners because they could slice off some to chew, which would help to keep coal dust from being swallowed. The Sunshine lamp usually has a double spout, because there had to be enough heat to melt the wax. The outer spout protected the inner from being cooled below the point where the wax would return to a solid form. Sunshine was not developed until later in the life of the wick lamp, but it quickly became the fuel of choice. A good form of cotton wicking was as necessary as good fuel, and many companies supplied this demand.

Installing a new wick in your lamp could be a humbling experience, but most miners soon became proficient. Wicks would regularly burn down to the point where they needed to be raised. Most miners would turn the lamp upside down and strike the base of the lamp at the point where the spout began, on the heel of their boot. This trick damaged many a lamp, and some manufacturers combated it by soldering a metal clip, called a bumper, to the lamp at this point to prevent damage.

Equally important was the method by which miners carried their fuel. Pocket flasks were common, but most chose a round flask, carried on the belt or by a strap hung over the shoulder. Some were quite small, but others were much larger. Miners usually carried drinking water in their lunch pails. If the miner carried a water flask, it normally had a cork stopper. Some flasks are found with cork gaskets and could have been used for oil or water.

Lamps were manufactured by 50 or more companies and many individuals. Regardless of what you called your lamp – tea kettle, tea pot, spout, oil wick - they were all similar in function.

Some of the more common manufacturers were the Anton Brothers of Monongalia, Pennsylvania, who had at least three concerns making lamps. Fred Zias of Frostburg, Maryland, was a large manufacturer, and Martin Hardsocg of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Ottumwa, Iowa, was another.

Prominent as well were the Trethaway Brothers of Parsons, Pennsylvania; C. George Company of Phillipsburg, Pennsylvania; and the Grier Brothers and W.A. Dunlap of Pittsburgh. T.F. Leonard of Scranton, Pennsylvania, was another prominent maker of lamps.

West Virginia was not left out as the Bluefield Hardware Company and the Miller Supply of Huntington had their own brand of lamps, but these are conceded to have been made by one of the larger companies and labeled for them. The Bluefield Hardware lamp is commonly acknowledged to have been made by Trethaway, and the Miller Supply lamp by Grier Brothers.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.