Back to the Land in Pocahontas County

By David Holtzman

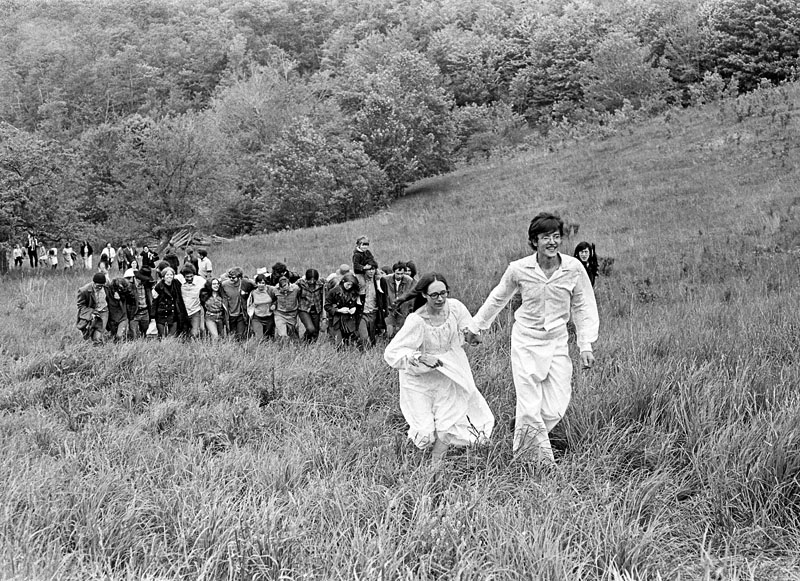

The back-to-the-land movement of the 1970's drew a large number of urban

newcomers to rural West Virginia. This group climbs a hill in Pocahontas

County to celebrate the wedding of Karl Hille and Barbara Lauster in 1970.

Photograph by Laurie Cameron.

In 1971, a state road crew cut down some big trees on Lobelia Road in Pocahontas County. The people who lived there promptly cut the trees into stacks of firewood. To their surprise, the wood soon disappeared. It turned out that a young couple new to the area had spotted the freshly chopped wood and hauled it away.

“They thought, ‘Oh boy, free firewood!’” remembers Beth Little, who moved to Lobelia Road around that time. “To the local people, they had just stolen their wood. Word got around pretty fast, and the couple was told they needed to take it back. It was ignorance, just not understanding how things worked.”

Situations like this were common in southern Pocahontas County and just over the line in Greenbrier County during the early 1970's, as large numbers of people moved to the area from big cities. It was one of several places in West Virginia that drew the attention of people in the back-to-the-land movement, mostly young people seeking a simpler way of life. By the middle of that decade, there were so many newcomers that they became a topic of conversation among natives of the area.

It was a big deal for so many new people to be moving to Pocahontas County, which had been losing people since the end of the logging boom in the 1920's. The trend was hardly limited to Pocahontas — only two counties in the state did not gain population during the 1970's. The back to the landers played a major role in this shift, but the trend did not last. By the end of the decade, many of the newcomers had moved back to the cities, typically because they couldn’t make a living here.

Of those who stayed, few took up skills traditional to the area, like farming or timbering. They found other ways to connect to their new communities, such as starting their own businesses, going to work for the schools, or joining the boards of local organizations. The newcomers used their imaginations to live out their dreams of a rural existence and slowly took on new identities as West Virginians.

The back-to-the-land movement occurred during a time of great upheaval in American culture, and many of the people who joined it wanted to “drop out” of mainstream society. To people in Pocahontas County, many of the newcomers appeared to fit the image they had of hippies, with long hair, beards, tattoos, and a “love child” attitude, as Evelyn Lewis, a lifelong resident of Friars Hole Road in Greenbrier County, recalls. Some locals were wary of the new crowd, based on the perception that the newcomers were just too different to blend in.

“Some of my friends steered completely away from them,” Evelyn says. “They didn’t know them and didn’t want to have anything to do with them. I found out, even though we don’t embrace the same beliefs religiously, that they were always good neighbors.”

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.