The World's Largest Clothespin Factory

By Beverly Steenstra

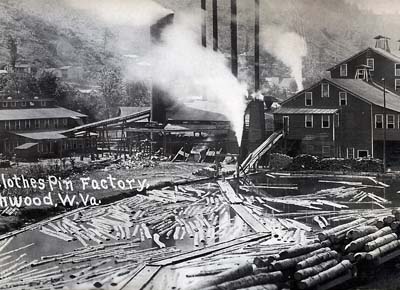

Thousands of cut trees, destined to become clothespins, were dumped into the factory pond. They were soaked and treated with a mysterious broth that removed the bark.

This 1908 photo shows flatbed train cars filled to capacity with timber. Note the log planks used as sidewalks. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the West Virginia State Archives.

I had a grandmother I never knew. Born in the Nicholas County town of Bays in 1920, Mabel May Jones disappeared after 1947, with only an occasional postcard making its way back to the family. May, as she was known, gave my birthmother, Donnie, and my Uncle Denny to the Children’s Home Society of West Virginia in 1946 and made a new home in Wilmington, Delaware, with Bluefield native Ted Chambers. In the late 1970s, Donnie and Denny started searching for their birthparents and eventually found their older brother and sister, Uncle Dale and Aunt Etta, and numerous aunts, uncles, and cousins living in Braxton, Webster, and Nicholas counties.

Nearly all of our newfound family shared bits and pieces of information about my grandmother, but little that was reliable or concrete. I joined the search in the 1990s but wasn’t much help. We did confirm one fact: May had worked at a clothespin factory in Richwood in the early 1940s. A clothespin factory? Who entertains thoughts about clothespin factories, especially in the 21st century? Well, this particular factory, operated by the Wallace Corporation, was the largest of its kind in the world!

A few years ago, I visited Aunt Etta, who was old enough to have solid memories of May. We sat at her kitchen table, trying to piece together wedding licenses, birth certificates, and what few photographs we had. We questioned how May could have just disappeared. Suddenly, Etta started, “Wait a minute, I’ll be right back.” She rummaged upstairs and returned with a handful of small clothespins! May had brought these for Etta to play with when Etta was a small child, and they had been long forgotten. When she handed them to me, I felt like I was holding something sacred. My grandmother had actually touched them and maybe even made them herself! Etta gave me four of the clothespins, which now sit beside me as I write this article.

In searching for my heritage, I’d stumbled upon an entire culture in rural America that once revolved around wood. The largest clothespin factory in the world began as the Dodge Clothespin Company in 1901. With the “rich wood” abundant in the area, and the expansion of railroads into Nicholas County, the enterprise held great promise. Because of its durability, beech was the best wood for clothespins, and there was plenty of beech enveloping Richwood. The company received a steady supply from the Cherry River Boom and Lumber Company and later from the U.S. Forest Service. Dr. Bob Henry Baber, current mayor of Richwood, speculates that the “crème de la crème” of the trees would have been milled into boards and that the mill’s “seconds, and thirds, and fourths, [which] are amazing . . . used to end up, frankly, at the clothespin factory.”

In 1923, the Dodge factory was purchased by a group of local businessmen and was the Steele-Wallace Corporation until 1928, when Steele sold his interest to Wallace. The enterprise was known as the Wallace Corporation until announcing its closure in 1958. It struggled into 1959, when the Forester Manufacturing Company of Farmington, Maine, which owned Wallace, sent the factory’s equipment to Sweden to begin operations there.

While clothespins were the main product and moneymaker, the factory also generated a variety of other items. In 1908, a wooden dish department was added, manufacturing wooden and paper trays through 1943. Toothpick production followed in the 1930s, and the humble round clothespin competed with the spring-type model and a square clothespin, which had the advantage of not rolling if it was dropped. The products had interesting brand names: Acme, Good Housekeeper, Maid of Honor, Top Fire (a rather peculiar choice for a highly flammable product). Housewives and photographers worldwide benefited from the four-million board feet of birch, beech, and hard maple timber churned out at the Richwood factory.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.