The Cockayne House:

A Preservation Effort by the Whole Community

By Larry Shockley

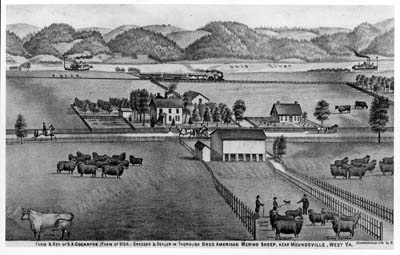

The Cockayne Farm and House were featured in the Illustrated Atlas of the Upper Ohio Valley, published by Titus, Simmons & Titus in 1877.

Note the proximity of the road (now West Virginia Route 2), railroad, and river. Courtesy of the West Virginia State Archives, Bob’s Lunch Collection.

The Cockayne Farmstead in Glen Dale is one of West Virginia’s great preservation stories. While the city of Glen Dale and the Marshall County Historical Society have taken lead roles, the project has been a team effort.

The Cockayne House dates to 1850, though the original farmstead is much older. Samuel Cockayne moved his family from Maryland to what is now the city of Glen Dale sometime between 1795 and 1798. The region was literally on the edge of America’s western frontier, but the Cockaynes weren’t alone.

In 1769, Ebenezer Zane settled at the confluence of the Ohio River and Wheeling Creek—several miles to the north. Then, in 1771, Joseph, Samuel, and James Tomlinson arrived at the confluence of the Ohio River and Grave Creek—about two miles south of the Cockayne Farmstead. Joseph Tomlinson later laid out lots for the town of Elizabethtown, which became part of Moundsville in 1866.

About the time Tomlinson was laying out his town, Samuel Cockayne was building a log cabin near Wheeling Pike (now West Virginia Route 2) on a 539-acre farm. While he was primarily a farmer, Cockayne also operated a tavern, known as the Andrew Jackson Inn. About 1850, his son Bennett built the Cockayne House that still stands at Glen Dale. Bennett served as postmaster in Moundsville and operated a general store in Elizabethtown. His oldest son, Alexander, opened Glen Dale’s first school in the house.

Another of Bennett’s sons, Samuel A. J.—whose footprints and initials are imprinted in the farmhouse’s stone hearth—would bring fame to the Cockayne Farmstead. Samuel A. J. purchased cattle, hogs, and other livestock from distant farms, but it was his ideas about sheep husbandry and marketing that brought Samuel A. J. renown. He stressed the importance of purity in the wool industry, as seen in his comments here to the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company: “There can be no permanent, profitable or satisfactory results secured in sheep husbandry without the use of pure bred rams. . . . The time has gone by where anything but pure blood will satisfy the intelligent wool grower.”

In 1868, Samuel A. J. Cockayne brought his first prized Merino rams to the farm. Merinos are sheep—originally imported from Spain—valued for the high quality and softness of their wool. According to a newspaper account from the time, Samuel A. J. spent $1,500—about $24,000 in today’s money—on one Spanish Merino ram from Vermont. In addition to purebred sheep, he also bought purebred pigs from Ohio.

In addition to emphasizing quality, Samuel A. J. was ahead of his time with marketing. Not merely satisfied with word of mouth about his prized livestock, he placed ads in distant newspapers to promote the days and times when he’d be selling his animals. Only eight years after purchasing his first Merino, Samuel A. J. gained international acclaim by winning first prize from the U.S. Centennial Commission at the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia. Two years later, he won notice for his sheep at the International Exhibition in Paris.

By 1877, the Cockayne Farm had become so prominent it was featured as a lithograph in the popular Illustrated Atlas of the Upper Ohio River Valley from Pittsburgh to Cincinnati—what many consider the “most extraordinary county atlas” of the 19th century.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.