Remember...

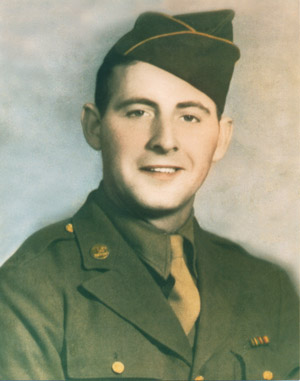

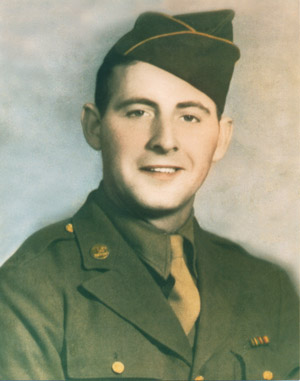

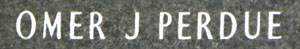

Omer Jessie Perdue

1922-1944

"If a man does his best, what else is there?"

|

Remember...Omer Jessie Perdue

|

Army Sergeant Omer Perdue received an Air Medal and two Purple Hearts for his service during World War II, but perhaps the most memorable honor came on July 4, 2010, when a bridge on West Virginia Route 152 at Lavalette in Wayne County was named for him and his brothers. Travelers through the area can now cross a bridge bearing the citation "Perdue Brothers Memorial Bridge - WWII Vets Walter, Riley, James, Norman, Omer, Earl."

Omer Jessie Perdue, a native of Union, Wayne County, West Virginia, was born in 1922 to the growing family of Edward Gerard and Grace Kisiah Akers Perdue that eventually would include eight brothers and five sisters: Edward Ervin (Ervin), Walter Alvin, William Riley (Riley), Charles Evan, James Ernest, Norman Russell, Omer, Earl Leonard, Geneva Belle, Pearl, Thelma Maud, Lucy Pauline (Pauline), and Ruby Bernice [information from 1920 and 1930 Federal Census records]. Ruby Perdue Steffen, the youngest child and last surviving member of the Perdue family, recalls that her father died when she was two years old, during the Great Depression, leaving her mother to care for and support the large brood. Omer Perdue, Ph.D., son of James, says of the family matriarch: "She was a determined, tenacious mother. The daunting task did not deter her from her duty. The family was held together through her grit and determination. Her children learned to persevere in the fact of hardship, and with will and sacrifice they succeeded together, living through and overcoming the obstacles of a very difficult time."

Ruby Steffen, in her book "Lil Ruby": Memoirs, details both the hardships and successes of the family. After her father's death, her mother was forced to sell livestock and farm equipment to pay funeral expenses. However, Edward had sold Stark trees, and, having planted hundreds of them on the farm, the family always had an abundance of fruit and vegetables. Walter then joined the Navy, and his fifteen-dollar-a-month allotment check was a great help in supporting the family.

Ruby also describes a premonition that her brother Omer had of the coming war. Early in December 1941, Omer told his mother of his dream that the United States was going to war and only the American flag was left standing.

U.S. Army World War II Enlistment Records, 1938-1946, indicate that Omer received a grammar school education and prior to his military service was engaged in "semiskilled occupations in mechanical treatment of metals (rolling, stamping, forging, pressing, etc.)." According to Mrs. Steffen, Omer went through the eighth grade at Big Creek School, but to go on to high school would have meant walking three miles one way to catch the bus to Wayne. She notes that when she came into Huntington and started high school, she was put into the "A" room and feels that Omer would have breezed through high school because he was so smart. Omer had a girlfriend he left behind, and she would eventually marry one of his best friends.

|

Seaman First Class Norman R. Perdue |

Pvt. James E. Perdue |

Navy Chief Commissary Steward Walter A. Perdue |

Staff Sgt. William R. ("Riley") Perdue |

The notion that World War II was fought by a "Band of Brothers" was no more true than in the Perdue family; six of the brothers would answer their country's call. At the time of Omer's death (December 23, 1944), Navy Chief Commissary Steward Walter was stationed in the South Pacific; Riley (William R.) was an Army staff sergeant serving somewhere in France; Army Private James was with the Medical Corps at Camp Upton, New York; and Seaman First Class Norman was in the Navy and stationed at Key West, Florida. Omer, who enlisted in the Army at Huntington, West Virginia, on February 15, 1943, was assigned to the 51st Infantry Battalion, 4th Armored Division, and was now a sergeant serving in France. Seaman Earl, the sixth brother to enlist, upon learning of his brother's death, joined the Navy during the last year of the war, when he was only sixteen, having persuaded his mother to sign papers that he was seventeen.

James' son Omer, in an address on the occasion of the dedication of the Perdue Brothers Memorial Bridge, described the family's service this way:

As the call to arms went out across the nation, it also came to Big Creek. Grace Akers Perdue had eight boys. Two could not serve. Ervin was above the age of service by 1941. Charles could not serve because of poor eyesight. However, six calls did come up to the log home at Big Creek. One by one, the Perdue brothers joined their countrymen in service to their nation.Some of the calls were formal notices:"From the President of the United States: Greetings, you are hereby directed to report. . . ." Others were calls from within, the inner summons of the soul to become part of that noble effort or, in the case of Earl, to take up arms to fill the gap left by a fallen brother. There were nonetheless, six heart-stirring occasions when Grace Perdue said goodbye, each time sending another son off to war.

World War II saw large migrations of folks from mid-South states like West Virginia and Kentucky to the industrial north. Several of the Perdue brothers had gone to Cleveland, Ohio, to work in a defense plant. When Omer was called to service, he wanted to join the Navy, but that would have meant he would leave immediately. Always concerned for his mother, he wanted to get word to her, so he went home for two weeks and then joined the Army. Ruby Steffen believes that, as the last eligible Perdue brother to enlist, Omer could have received a deferment, but that was not in his nature. He trained at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and then in Texas, before being shipped to Europe.

Like many of his fellow soldiers, Omer would spend his waiting time in England in correspondence with family. Writing to his sister Pearl from England in January 1944, Omer thanks her for the candy she has sent:

And you write once in a while. I don't think I've heard from you since I came in the army. Well it is getting late and I'm sleepy as the devil, so I'll sign off and go to bed. Be a good girl. Write soon and often and give me all the news. By-Bye, much love.

Your Brother,I was almost starved for some good candy since it's been some time since I've had any. I could hardly wait to get it open to get a piece of it. . . . Well I guess I'd better tell where I'm at now if you don't already know. I'm now in England, and it is a swell place to be. Especily at a time like this. . . . But I'd still take the good old states. One can have a pretty good time over hear cheap if he knows how to count. [He proceeds to describe the English monetary system.] A lot of the boys don't know to much about their money, and they [the English] cheat them out of half of their money in giving them change. . . .

Omer

Plaque in Bastogne, Belgium, commemorating members of the 4th Armored Division who lost their lives |

A few months later, Omer would be in the thick of battle. Wounded and hospitalized, he received a Purple Heart, but was pressed back into service because of the desperate need for men to wage the Allied offensive best known as the Battle of the Bulge. It was in this action he was killed on a half-track at Bastogne in Belgium. (More on the Battle of the Bulge can be found at http://www.army.mil/botb/ or http://worldwar2history.info/Bulge/. A detailed account of this military campaign is Hugh M. Cole's online book The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge [http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/7-8/7-8_cont.htm].) |

In her home, Ruby Perdue Steffen has a "memory room," where she recalls her brothers' service to their country and keeps mementos of their lives, but because she had a hard time looking at Omer's medals and the letter from President Roosevelt announcing his death, those items were passed on to the nephew who is Omer's namesake. Writing in the Huntington Herald Dispatch on December 22, 2009, Bill Rosenberger notes that Ruby was closest to Omer, and not just in age. "I wanted to go to school all the time," Ruby stated, "and Omer would carry me to school on his back." Though she was only fourteen at the time of his death in the Battle of the Bulge, she vividly remembers the effect the death had on her mother, who would never be quite the same. Nevertheless, Ruby said her mother signed for her brother Earl to enlist, adding, "My mother was always waiting for another telegram. After the other boys came home, she got better."

Information contributed by Omer's sister Ruby Perdue Steffen, who also provided the photographs of her brothers, and nephew and namesake Omer Perdue, Ph. D. Article by Patricia Richards McClure

West Virginia Archives and History welcomes any additional information that can be provided about these veterans, including photographs, family names, letters and other relevant personal history.